Gilad Bracha recently posted an article “Bits of History, Words of Advice” that talks about the incredible influence of Smalltalk but bemoans the fact that:

…today Smalltalk is relegated to a small niche of true believers. Whenever two or more Smalltalkers gather over drinks, the question is debated: Why?

(All block quotes are from Gilad’s article unless otherwise noted.)

Smalltalk actually had a surge of commercial popularity in the first half of the 1990s but that interest evaporated almost instantaneously in 1996. Most of the Gilad’s article consists of his speculations on why that happened. I agree with many of Gilad’s takes on this subject, but his involvement and perspective with Smalltalk started relatively late in the commercial Smalltalk lifecycle. I was there pretty much at the beginning so it seems appropriate to add some additional history and my own personal perspective. I’ll be directly responding to some of Gilad’s points, so you should probably read his post before continuing.

Let’s Start with Some History

Gilad worked on the Strongtalk implementation of Smalltalk that was developed in the mid-1990s. His post describes the world of Smalltalk as he saw it during that period. But to get a more complete understanding we will start with an overview of what had occurred over the previous twenty years.

1970-1979: Creation

Starting in the early 1970s the early Smalltalkers and other Xerox PARC researchers invented the concepts and mechanisms of Personal Computing, most of which are still dominant today. Guided by Alan Kay’s vision, Dan Ingalls along with Ted Kaehler, Adele Goldberg, Larry Tesler, and other members of the PARC Learning Research Group created Smalltalk as the software for the Dynabook, their aspirational model of a personal computer. Smalltalk wasn’t just a programming language—it was, using today’s terminology, a complete software application platform and development environment running on the bare metal of dedicated personal supercomputers. During this time, the Smalltalk language and system evolved through at least five major versions.

1980-1984: Dissemination and Frustration

In the 1970s, the outside world only saw hints and fleeting glimpses of was what was going on within the Learning Research Group. Their work influenced the design of the Xerox Star family of office machines and after Steve Jobs got a Smalltalk demo he hired away Larry Tesler to work on the Apple Lisa. But the LRG team (later called SCG for Software Concepts Group) wanted to directly expose their work (Smalltalk) to the world at large. They developed a version of their software, Smalltalk-80, that would be suitable for distribution outside of Xerox and wrote about it in a series of books and a special issue of the widely read Byte magazine. They also made a memory snapshot of their Smalltalk-80 implementation available to several companies that they thought had the hardware expertise to build the microcoded custom processors that they thought were needed to run Smalltalk. The hope was that the companies would design and sell Smalltalk-based computers similar to the one they were using at Xerox PARC.

But none of the collaborators did this. Instead of building microcoded Smalltalk processors they used economical mini-computers or commodity microprocessor-based systems and coded what were essentially simple software emulations of the Xerox super computer Smalltalk machines. The initial results were very disappointing. They could nominally run the Xerox provided Smalltalk memory image but at speeds 10–100 times slower than the machines being used at PARC. This was extremely frustrating as their implementations were too slow to do meaningful work with the Smalltalk platform. Most of the original external collaborators eventually gave up on Smalltalk.

But a few groups, such as me and my colleagues at Tektronix, L Peter Deutsch and Alan Schiffman at Xerox, and Dave Ungar at UC Berkley developed new techniques leading to drastically better Smalltalk-80 performance using commodity microprocessors with 32-bit architectures.

At the same time Jim Anderson, George Bosworth, and their colleagues, working exclusive from the Byte articles independently developed a new Smalltalk that could usefully run on the original IBM PC with its Intel 8088 processor.

1985-1989: Productization

By 1985, it was possible to actually use Smalltalk on affordable hardware and various groups went about releasing Smalltalk products. In January 1985 my group at Tektronix shipped the first of a series of “AI Workstations” that were specifically designed to support Smalltalk-80. At about the same time Digitalk, Anderson’s and Bosworth’s company, shipped Methods—their first IBM PC Smalltalk product. This was followed by their Smalltalk/V products, whose name suggested a linkage to Alan Kay’s Vivarium project. Servio Logic introduced GemStone, an object-oriented data base system based on Smalltalk. In 1987 most of the remaining Xerox PARC Smalltalkers, led by Adele Goldberg, spun-off into a startup company, ParcPlace Systems. Their initial focus was selling Smalltalk-80 systems for workstation class machines.

Dave Thomas’ Object Technology International (OTI) worked with Digitalk to create a Macintosh version of Smalltalk/V and then started to develop the Smalltalk technology that would eventually be used in IBM’s VisualAge products. Tektronix, working with OTI, started developing two new families of oscilloscopes that used embedded Smalltalk to run its user interface. Both OTI and Instantiations, a Tektronix spin-off, started working on tools to support team-scale development projects using Smalltalk.

1990-1995: Enterprise Smalltalk

As many software tools vendors discovered over that period, it takes too many $99 sales to support anything larger than a “lifestyle” business. In 1990, if you wanted to build a substantial software tools business you had to find the customers who spent substantial sums on such tools. Most tools vendors who stayed in business discovered that most of those customers were enterprise IT departments. Those organizations, used to being IBM mainframe customers, often had hundreds of in-house developers and were willing to spend several thousand dollars per initial developer seat plus substantial yearly support fees for an effective application development platform.

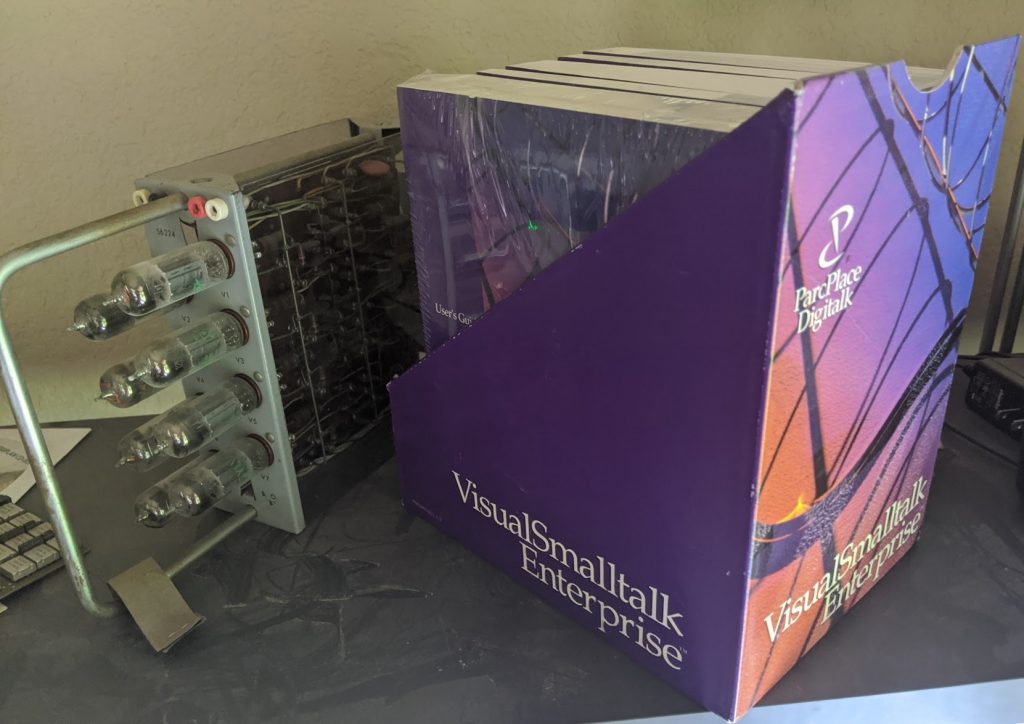

At that time, many enterprise IT organizations were trying to transition from mainframe driven “green-screen” applications to “fat clients” with modern Mac/Windows type GUI interfaces. The major Smalltalk vendors positioned their products as solutions to that transition problem. This was reflected in their product branding, ParcPlace Systems’ ObjectWorks was renamed as VisualWorks. Digitalk’s Smalltalk/V became VisualSmalltalk Enterprise, IBM used OTI’s embedded Smalltalk technologies as the basis of VisualAge. Smalltalk was even being positioned in the technical press and books as the potential successor to COBOL:

Dave Thomas’ 1995 article “Travels with Smalltalk” is an excellent survey of the then current and previous ten years of commercial Smalltalk activity. Around the time it was published, IBM consolidated its Smalltalk technology base by acquiring Dave’s OTI, and Digitalk merged with ParcPlace Systems. That merger was motivated by their mutual fear of IBM Smalltalk’s competitive power in the enterprise market.

1996-Present: Retreating to the Fringe

Over six months in 1996, Smalltalk’s place in the market changed from the enterprise darling COBOL replacement to yet another disappointing tool with a long tail of deployed applications that needed to be maintained.

The World Wide Web diverted enterprise attention away from fat clients and suddenly web thin clients were the hot new technology. At the same time Sun Microsystems’ massive marketing campaign for Java convinced enterprises that Java was the future for both web and standalone client applications. Even though Java never delivered on its client-side promises, the commercial Smalltalk vendors were unable to counter the Java hype cycle and development of new Smalltalk-based enterprise applications stopped. The merged ParcPlace-Digitalk rapidly declined and only survived for a couple more years. IBM quickly pivoted its development attention to Java and used the development environment expertise it had acquired from OTI to create Eclipse.

Niche companies assumed responsibility for support of the legacy enterprise Smalltalk customers with deployed applications. Cincom picked up support for VisualWorks and Visual Smalltalk Enterprise customers, while Instantiations took over supporting IBM’s VisualAge Smalltalk. Today, twenty five years later, there are still hundreds of deployed legacy enterprise Smalltalk applications.

Dan Ingalls at Apple in 1996 used an original Smalltalk-80 virtual image to bootstrap Squeak Smalltalk. Dan, Alan Kay, and their colleagues at Apple, Disney, and some universities used Squeak as a research platform, much as they had used the original Smalltalk at Xerox PARC. Squeak was released as open source software and has a community of users and contributors throughout the world. In 2008, Pharo was forked from Squeak, with the intent of being a streamlined, more industrialized, and less research focused version of Smalltalk. In addition, several other Smalltalks have been created over that last 25 years. Today Smalltalk still has a small, enthusiastic, and somewhat fragmented base of users

Why Didn’t Smalltalk Win?

Gilad in his article, lists four major areas of failure of execution by the Smalltalk community that led to its lack of broad long term adoption. Let’s look at each of them and see where I agree and disagree.

Lack of a Standard

But a standard for what? What is this “Smalltalk” thing that wasn’t standardized? As Gilad notes, there was a reasonable degree of de facto agreement on the core language syntax, semantics and even the kernel class protocols going back to at least 1988. But beyond that kernel, things were very different.

Each vendor had a slightly different version – not so much a different language, as a different platform.

And these platforms weren’t just slightly different. They were very different in terms of everything that made them a platform. The differences between the Smalltalk platforms were not like those that existed at the time between compilers like GCC and Microsoft’s C/C++. A more apt analog would be the differences between platforms like Windows, Solaris, various Linux distributions, and Mac OSX. A C program using the standard C library can be easily ported among all these platform but porting a highly interactive GUI C-based application usually required a major rewrite.

The competing Smalltalk platform products were just as different. It was easy enough to “file out” basic Smalltalk language code that used the common kernel classes and move it to another Smalltalk product. But just like the C-implemented platforms, porting a highly interactive GUI application among Smalltalk platforms required a major rewrite The core problem wasn’t the reflective manner in which Smalltalk programs were defined (although I strongly agree with Gilad that this is undesirable). The problem was that all the platform services that built upon the core language and kernel classes—the things that make a platform a platform—were different. By 1995, there were at three major and several niche Smalltalk platforms competing in the client application platform space. But by then there was already a client platform winner—it was Microsoft Windows.

Business Model

Smalltalk vendors had the quaint belief in the notion of “build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door”. Since they had built a vastly better mousetrap, they thought they might charge money for it.

…Indeed, some vendors charged not per-developer-seat, but per deployed instance of the software. Greedy algorithms are often suboptimal, and this approach was greedier and less optimal than most.

This may be an accurate description of the business model of ParcPlace Systems, but it isn’t a fair characterization of the other Smalltalk vendors. In particular, Digitalk started with a $99 Smalltalk product for IBM PCs and between 1985 and 1990 built a reasonable small business around sub $500 Smalltalk products for PCs and Macs. Then, with VC funding, it transitioned to a fairly standard enterprise focused $2000+ per seat plus professional services business model. Digitalk never had deployment fees. I don’t believe that IBM did either.

The enterprise business model worked well for the major Smalltalk vendors—but it became a trap. When you acquire such customers you have to respond to their needs. And their immediate needs were building those fat-client applications. I remember with dismay the day at Digitalk when I realized that our customers didn’t really care about Smalltalk, or object-based programming and design, or live programming, or any of the unique technologies Smalltalk brought to the table. They just wanted to replace those green-screens with something that looked like a Windows application. They bought our products because our (quite successful) enterprise sales group convinced them that Smalltalk was necessary to build such applications.

Supporting those customer expectations diverted engineering resources to visual designers and box & stick visual programming tools rather than important down-stream issues such as team collaborative development, versioning, and deployment. Yes, we knew about these issues and had plans to address them, but most resources went to the immediate customer GUI issues. So much so that ParcPlace and Digitalk were blindsided and totally unprepared to compete when their leading enterprise customers pivoted to web-based thin-clients.

Performance

Smalltalk execution performance had been a major issue in the 1980s. But by the mid 1990s every major commercial Smalltalk had a JIT-based virtual machine and a multi-generation garbage collector. When “Strongtalk applied Self’s technology to Smalltalk” it was already practical.

While those of us working on Smalltalk VMs loved to chase C++ performance our actual competition was PowerBuilder, Visual Basic, and occasionally Delphi. All the major Smalltalk VMs had much better execution performance than any of those. Microsoft once even made a bid to acquire Digitalk, even though they had no interest in Smalltalk. They just wanted to repurpose the Smalltalk/V VM technology to make Visual Basic faster.

But as Gilad points out, raw speed is seldom an issue. Particularly for the fat client UIs that were the focus of most commercial Smalltalk customers. Smalltalk VMs also had much better performance than the other dynamic languages that emerged and gained some popularity during the 1990s. Perl, Python, Ruby, PHP all had, and as far as I know still have, much poorer execution performance than 1995 Smalltalks running on comparable hardware.

Memory usage was a bigger issues. It was expensive for customers to have to double the memory in PCs to effectively run commercial Smalltalk. But Moore’s law quickly overcame that issue.

It’s also worth dwelling on the fact that raw speed is often much less relevant than people think. Java was introduced as a client technology (anyone remember applets?). The vision was programs running in web pages. Alas, Java was a terrible client technology. In contrast, even a Squeak interpreter, let alone Strongtalk, had much better start up times than Java, and better interactive response as well. It also had much smaller footprint. It was a much better basis for performant client software than Java. The implications are staggering.

Would Squeak (or any mid-1990s version of Smalltalk) have really fared better than Java in the browser? You can try it yourself by running a 1998 version of Squeak right now in your browser: https://squeak.js.org/demo/simple.html. Is this what web developers needed at that time?

Java’s problem as a web client was that it wanted to be it’s own platform. Java wasn’t well integrated into the HTML-based architecture of web browsers. Instead, Java treated the browser as simply another processor to host the Sun-controlled “write once, run [the same] everywhere ” Java application platform. It’s goal wasn’t to enhance native browser technology—it’s goal was to replace them.

Interaction with the Outside World

Because of their platform heritage, commercial Smalltalk products had similar problems to those Java had. There was an “impedance mismatch” between the Smalltalk way of doing things and the dominant client platforms such as Microsoft Windows. The non-Smalltalk-80 derived platforms (Digitalk and OTI/IBM) did a better job than ParcPlace Systems at smoothing that mismatch.

Windowing. Smalltalk was the birthplace of windowing. Ironically, Smalltalks continued to run on top of their own idiosyncratic window systems, locked inside a single OS window.

Strongtalk addressed this too; occasionally, so did others, but the main efforts remained focused on their own isolated world, graphically as in every other way.

This describes ParcPlace’s VisualWorks, but not Digitalk’s Visual Smalltalk or IBM’s VisualAge Smalltalk. Applications written for those Smalltalks used native platform windows and widgets, just like other languages. Each Smalltalk vendor supplied their own higher-level GUI frameworks. Those frameworks were different from each other and from frameworks used with other languages. Digitalk’s early Smalltalk products for MSDOS supplied their own windowing systems, but Digitalk’s Windows and OS/2 products always used the native windows and graphics.

Source control. The lack of a conventional syntax meant that Smalltalk code could not be managed with conventional source control systems. Instead, there were custom tools. Some were great – but they were very expensive.

Both IBM and Digitalk bundled source control systems into their enterprise Smalltalk products which were competitively priced with other enterprise development platforms. OTI/IBM’s Envy source control system successfully built upon Smalltalk’s traditional reflective syntax and stored code in a multiuser object database. OTI also sold Envy for ParcPlace’s VisualWorks but lacked the pricing advantage of bundling. Digitalk’s Team/V unobtrusively introduced a non-reflective syntax and versioned source code using RCS. Team/V could forward and backwards migrate versions of Smalltalk “modules” within an running virtual image.

Deployment. Smalltalk made it very difficult to deploy an application separate from the programming environment.

As Gilad describes, extracting an application from its development environment could be tricky. But both Team/V and Envy included tools to help developers do this. Team/V support the deployment of applications as Digitalk Smalltalk Link Libraries (SLLs) which were separable virtual image segments that could be dynamically loaded. Envy, which originally was designed to generate ROM-based embedded applications, had rich tools for tree-shaking a deployable application from a development image.

Gilad also mentioned that “unprotected IP” was a deployment concern that hindered Smalltalk acceptance. This is presumably because even if source code wasn’t deployed with an application it was quite easy to decompile a Smalltalk bytecoded method back into human readable source code. Indeed, potential enterprise customers would occasionally raise that as a concern. But, it was usually as a “what about” issue. Out of hundreds of enterprise customers we dealt with at Digitalk, I can’t recall a single instance where unprotected IP killed a deal. If it had been, we would have done something about this as we knew of various techniques that could be used to obfuscate Smalltalk code.

“So why didn’t Smalltalk take over the world?”

Smalltalk did something more important than take over the world—it define the shape of the world! Alan Kay’s Dynabook vision of personal computing didn’t come with a detailed design document describing all of its features and how to create it. To make the vision concrete, real artifacts had to be invented.

Smalltalk was the software foundation for “inventing the future” Dynabook. The Smalltalk programming language went through at least five major revisions at Xerox PARC and evolved into the software platform of the prototype Dynabook. Using the Smalltalk platform, the fundamental concepts of a personal graphic user interface were first explored and refined. Those initial concepts were widely copied and further refined in the market resulting in the systems we still use today. Smalltalk was also the vector by which the concepts of object-oriented programming and design were introduced to a world-wide programming community. Those ideas dominated for at least 25 years. From the perspective of its original purpose, Smalltalk was a phenomenal success.

But, I think Gilad’s question really is: Why didn’t the Smalltalk programming language become one of the most widely used languages? Why isn’t it in the top 10 of the Tiobe Index?

Gilad’s entire article is essentially about answering that question, and he summarizes his conclusions as:

With 20/20 hindsight, we can see that from the pointy-headed boss perspective, the Smalltalk value proposition was:

Pay a lot of money to be locked in to slow software that exposes your IP, looks weird on screen and cannot interact well with anything else; it is much easier to maintain and develop though!

On top of that, a fair amount of bad luck.

There are elements of truth in all of those observations, but I think they miss what really happened with the rise and fall of commercial Smalltalk:

- Smalltalk wasn’t just a language; it was a complete personal computing platform. But by the time affordable personal computing hardware could run the Smalltalk platform, other less demanding platforms had already dominated the personal computing ecosystem.

- Xerox Smalltalk was built for experimentation. It was never hardened for wide use or reliable application deployment.

- Adapting Smalltalk for production use required large engineering teams and in the late 1980s no deep-pocketed large companies were willing to make that investment. Other than IBM and HP, the large computing companies that could have helped ready Smalltalk for production use took other paths.

- Small companies that wanted to harden Smalltalk needed to find a business model that would support that large engineering effort. The obvious one was the enterprise application development market.

- To break into that market required providing a solution to an important customer problem. The problem the companies latched on to was enterprise migration from green-screens to more modern looking fat-client applications.

- Several companies had considerable success in taking Smalltalk to the enterprise market. But these were demanding and fickle customers and the Smalltalk companies became hyper focused on fulfilling their fat-client commitments.

- With that focus, the Smalltalk companies were completely unprepared in 1996 to deal with the sudden emergence of the web browser platform and its use within enterprises. At the same time, Sun, a much larger company than any of the Smalltalk-technology driven companies spent vast sums to promote Java as the solution for both web and desktop client applications.

- Enterprises diverted their development tool purchases from Smalltalk companies to new businesses who promised web and/or Java based solutions.

- Smalltalk revenues rapidly declined and the Smalltalk focused companies failed.

- Technologies that have failed in the marketplace seldom get revived.

Smalltalk still has its niche uses and devotees. Sometimes interesting new technologies emerge from that community. Gilad’s Newspeak is a quite interesting rethinking of the language layer of traditional Smalltalk.

Gilad mentioned Smalltalk’s bad luck. But I think it had better than average luck compared to most other attempts to industrialize innovative programming technologies. It takes incredible luck and timing to become of one of the world’s most widely used programming languages. It’s such a rare event that no language designer should start out with that expectation. You really should have some other motivation to justify your effort.

But my question for Newspeak and any similar efforts is: What is your goal? What drives the design? What impact do you want to have?

Smalltalk wasn’t created to rule the software world, it was created to enable the invention of a new software world. I want to hear about compelling visions for the next software world and what we will need to build it. Could Newspeak have such a role?